Understanding Trade Dress Drawings and USPTO Requirements: A Practical Guide for Protecting Product Design and Packaging (2025 Update)

Wilson Whitaker Rynell – Dallas Trademark, IP & Business Litigation Attorneys

Trade dress protection sits at the intersection of law, branding, and product design. It is one of the most misunderstood—and most powerful—forms of intellectual property protection in the United States. But the strength of a trade dress claim begins long before litigation. It starts with how you present your design to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Whether you are seeking to protect the configuration of a product, the shape of a container, the look and feel of packaging, or a distinctive non-traditional design element, understanding USPTO drawing requirements is essential. A single missed dotted line or the wrong formatting choice can derail an application, trigger costly refusals, or undermine enforceability down the road. This article brings the statutory framework to life by linking USPTO rules to real-world litigation principles—distinctiveness, secondary meaning, functionality, and consumer confusion—so you can understand how these concepts work together to protect (or defeat protection for) trade dress.

What Makes Trade Dress Protectable?

At its foundation, trade dress captures the “total image and overall appearance” of a product or its packaging. It is the visual impression that makes a product instantly recognizable before a consumer ever sees a logo or reads a label. Courts have treated trade dress broadly, extending protection to the distinctive features of a restaurant interior, the contours of a perfume bottle, the layout of a retail store, and even thematic décor that gives a business its signature look.

Trade dress can include a wide range of design elements working together:

- Shape, size, or configuration

- Color or color combinations

- Texture or surface finishes

- Packaging choices

- Graphic elements, themes, and ornamental presentation

Yet not every design choice is eligible for protection. Before the USPTO will register trade dress—or a court will enforce it—the owner must demonstrate that the design either:

- Is inherently distinctive, meaning its primary purpose is to signal source rather than describe the product, or

- Has acquired distinctiveness, also known as secondary meaning, through consistent use and consumer recognition over time.

Even then, a final barrier remains: the design cannot be functional. If a feature exists chiefly because it makes a product stronger, cheaper, more efficient, or more desirable in a way that competitors need to replicate to compete fairly, the law places it outside the scope of trademark protection. Functionality—whether utilitarian or aesthetic—is a complete bar to trade dress rights.

Understanding this balance between creativity and legal constraints is essential. Trade dress protection rewards design choices that communicate brand identity, not those that give a product a competitive edge in how it performs.

Inherent Distinctiveness: When a Design Speaks for Itself

Courts rarely call something “inherently distinctive,” and for good reason. To qualify, the trade dress must immediately signal “source,” not simply “design.” The Supreme Court illustrated this in a case involving a Mexican restaurant chain whose décor featured vivid murals, neon stripes, pottery, and brightly colored umbrellas. Taken together, those elements were so unusual and memorable that customers perceived them as a signature look—something inherently tied to the brand.

Contrast that with the “Cuffs & Collar” design used by Chippendales dancers. The court found it lacked inherent distinctiveness—largely because it evoked a well-known cultural reference (the Playboy bunny costume) and therefore didn’t immediately designate source.

Most product shapes and packaging do not meet this high bar.

"Alternatively, the Board concluded that the Cuffs & Collar mark was not unique or unusual in the particular field of use because it was inspired by the ubiquitous Playboy bunny suit, which included cuffs, a collar and bowtie, a corset, and a set of bunny ears. Id . at 1546. Finally, the Board concluded that the Cuffs & Collar mark “was a refinement of an existing form of ornamentation for the particular class of services,” based on the same evidence discussed in the treatment of the first two Seabrook factors. Id. at 1542. The dissent disagreed, concluding that the Cuffs & Collar mark was in fact inherently distinctive. Id. at 1544-45. Chippendales timely appealed, and this court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a)(4)(B)." IN RE: CHIPPENDALES USA (2010)

Indeed, in Wal-Mart v. Samara Brothers, the Supreme Court held that product design can never be inherently distinctive. As a matter of law, product configurations must show evidence of secondary meaning to be protectable. This means a perfume bottle, a wristwatch face, or a container shape cannot rely on “distinctive design alone” as proof of origin. They need evidence of consumer association.

Secondary Meaning: When the Market Learns to Recognize Your Design

A design acquires secondary meaning when consumers begin to associate its primary significance with a single source. Courts analyze several types of evidence, including:

- The length and exclusivity of use

- Advertising specifically promoting the design itself (not just the product)

- Consumer surveys

- Sales success

- Media recognition

- Competitor attempts to copy the design

Consider Calvin Klein’s “Eternity” perfume bottle. Although the bottle had been advertised and was registered, a court found the trade dress weak. The design closely resembled many other perfume bottles—hourglass shapes, clear glass, similar caps. Even consumer surveys showed only about 21% recognition. Without stronger proof, the design lacked secondary meaning.

"The high quality ETERNITY perfume is sold in a bottle that is a registered trademark[2] owned by Conopco and held by plaintiff Calvin Klein Cosmetic Corporation. See id. at 65, 78. It is "elegantly dimensioned" and made of "high clarity flint glass." See PX-1. It has "bevelled edges, and heavy walled distribution." Id. The design "gives the illusion of a bottle within a bottle, with softly contoured sides, and the fragrance free floating in the inner bottle cavity." Id. The bottle's cap is a squared-off silver-colored stopper. See Tr. at 119-20." Conopco, Inc. v. Cosmair, Inc., 49 F. Supp. 2d 242 (S.D.N.Y. 1999)

REGISTRATION ALONE DOES NOT GUARANTEE

TRADE DRESS PROTECTION

Trade dress must live in the minds of consumers, not merely in the USPTO.

Understanding Functionality: The Line Between Design and Protectable Trade Dress

Trade dress does not protect every clever or aesthetically pleasing design. The law draws a firm boundary around functionality, and any feature that crosses that line is automatically excluded from protection—no matter how distinctive or recognizable it may be.

A design feature is considered functional if it satisfies any of the following:

- It is essential to the use or purpose of the product.

- It affects the cost or quality of the product, such as making it stronger, cheaper, or easier to manufacture.

- It provides a significant competitive advantage, including advantages rooted purely in appearance.

This last category—often called aesthetic functionality—is one of the most misunderstood. Businesses understandably assume that if a feature doesn’t change how the product works, it must be protectable. But the law focuses on competitive fairness, not artistic merit.

If a visual feature gives the brand an edge that competitors cannot reasonably replicate without being placed at a disadvantage, courts may deem it functional.

A leading example comes from Brunswick Corp. v. British Seagull Ltd. There, the court held that black outboard motors were functional even though the color did not alter performance. Why? Because black made the motors look smaller and allowed them to coordinate easily with a wide variety of boat designs. That aesthetic edge—making the product more appealing and versatile—was considered a real competitive advantage. As a result, the color could not be monopolized as trade dress. The takeaway is simple but vital: If granting a company exclusive rights to a design feature would hinder competition, the law treats that feature as functional. Protectable trade dress must do more than attract the eye; it must serve primarily as a source identifier rather than a marketplace advantage.

How Drawing Requirements Define the Scope of Your Trade Dress Claim

When a business seeks trade dress protection, the most important document it submits to the USPTO is not the description—it’s the drawing. Under 37 C.F.R. § 2.52 and the Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP), the drawing sets the precise legal boundaries of what the applicant is claiming as its trademark. In other words, the drawing functions as the fence line around the property you want the law to protect.

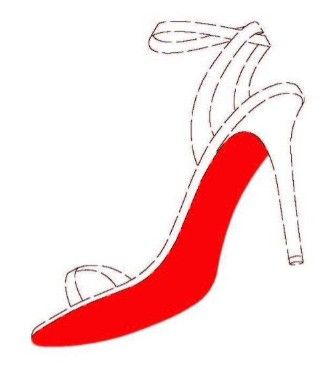

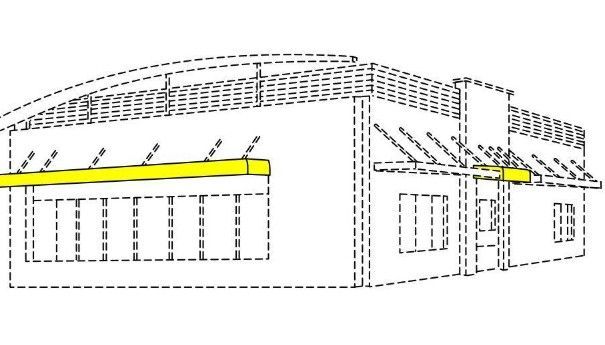

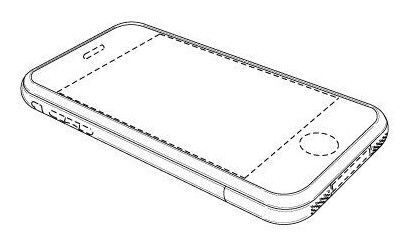

The USPTO requires applicants to distinguish between claimed and unclaimed features using two simple but rigid conventions:

- Solid lines identify the elements of the design that the applicant is claiming as trade dress.

- Broken (dashed) lines identify what is not being claimed—whether because it is functional, unprotectable, or merely included to show the context in which the claimed design appears.

These rules are not just bureaucratic detail. They perform an essential gatekeeping function. By forcing applicants to visually separate protectable features from unprotectable ones, the USPTO prevents brand owners from overreaching—that is, from attempting to monopolize aspects of a product’s configuration that the law reserves for open competition.

In practice, a carefully prepared drawing can determine whether a trade dress application survives examination, whether it can be enforced in court, and whether it becomes a meaningful asset or merely a decorative filing. Precise line work ensures the applicant claims only what the law permits, no more and no less, and it gives courts a clear blueprint should enforcement become necessary.

Trade Dress Litigation: Confusion, Distinctiveness, and Dilution

Once registered, trade dress may be enforced against competitors—but at the heart of any trade dress infringement claim is one central question: Are consumers likely to be confused about the source of the goods? Courts do not answer this with a single snapshot comparison. Instead, they weigh a series of interrelated factors that collectively paint a picture of how the average buyer would interpret the competing designs.

Consumer confusion analysis hinges on:

- The strength of the trade dress

- The similarity of the designs

- The similarity of the products

- Evidence of actual confusion

- The intent of the defendant

Importantly, even when two designs appear visually similar, a trade dress claim will fail unless the plaintiff can show that consumers are likely to believe the products come from the same source. Similarity alone is not enough; what matters is how that similarity affects real-world purchasing decisions.

Trade Dress Dilution Claims

Federal law gives owners of famous trade dress an additional tool beyond standard infringement: the right to bring a dilution claim. This remedy is not available to every brand owner. To qualify, the trade dress must satisfy three demanding criteria. First, the design must be non-functional, meaning it cannot be essential to how the product works or provide a competitive advantage. Second, the trade dress must be widely recognized by the general consuming public—a level of fame comparable to the most iconic brands. Finally, the fame must stem from the trade dress itself, not simply from a well-known name, logo, or other associated word marks

Simply, to succeed, the design must be:

- Non-functional

- Widely recognized by the general consuming public

- Famous as its own trade dress, not merely because of associated word marks

Because few product designs achieve this level of notoriety, dilution claims are uncommon. But when the standard is met, the cause of action can be exceptionally powerful. Unlike traditional infringement, which hinges on whether consumers are likely to be confused, dilution focuses on whether the defendant’s use will blur or tarnish the uniqueness of a truly famous trade dress. In the right case, it becomes a formidable weapon to protect the distinct identity of a brand’s visual presentation.

Trade Dress FAQs

Is registering trade dress the same as proving it is distinctive?

No. Registration does not guarantee strength. Courts may still find the trade dress weak or lacking secondary meaning.

What happens if my drawing shows functional features in solid lines?

The USPTO may refuse the application or require you to amend the drawing to avoid claiming unprotectable features.

Can I register the shape of my product?

Yes, but only with strong evidence of secondary meaning and only if the design is not functional.

Why are broken lines so important in USPTO drawings?

Broken lines clarify what is not being claimed. They prevent overreach and help examiners, courts, and competitors understand the scope of the mark.

Is color as trade dress hard to protect?

Extremely. You must prove non-functionality and consumer association—usually through years of advertising and market presence.

Can I win a trade dress infringement case without a registration?

Yes. Federal law protects unregistered trade dress, but you must prove distinctiveness and likelihood of confusion—often a higher burden.

What type of evidence best shows secondary meaning?

Consumer surveys and long-term, exclusive use are often the strongest. Media coverage, advertising, and sales data also play an important role.

Why Trade Dress Rules Matter for Brand Owners

Businesses often devote years—sometimes decades—to shaping the look and feel of their products. Packaging choices, color schemes, container shapes, and product configurations all become part of a brand’s identity. Yet many companies don’t realize that trade dress protection comes with strict legal boundaries, and even a small error early in the process can undermine the ability to enforce those rights later. Something as simple as using broken lines incorrectly, claiming too much, or failing to document how consumers recognize your design can weaken or even forfeit protection. Courts and the USPTO expect a clear showing that the trade dress is non-functional, consistently used, and—if not inherently distinctive—supported by evidence of secondary meaning. Without that foundation, enforcement becomes an uphill battle.

A truly effective trade dress strategy is not just creative; it is deliberate. It harmonizes several elements:

- Creativity, to ensure the design is memorable and capable of distinguishing the brand.

- Legal compliance, including proper drawings, precise claim scope, and adherence to USPTO standards.

- Market recognition, built through consistent commercial use and documentation over time.

- Consumer perception, which ultimately determines whether the design signals source in the minds of buyers.

At

Wilson Whitaker Rynell, we work with companies to build this strategy from the outset—guiding design teams on how to develop protectable trade dress, preparing and prosecuting USPTO applications that withstand scrutiny, and enforcing those rights through infringement and dilution litigation in federal court. Thoughtful planning at the beginning often becomes the difference between a design that is merely attractive and one that is legally defensible.

Legal Solutions For You | Wilson Legal Group

Looking for Top Legal Representation in the Dallas, Houston or Austin? Contact Wilson Legal Group!

At Wilson Legal Group, we are dedicated to providing exceptional trade dress legal services.

Need help with business litigation, resolving business disputes, or securing trademark, trade dress, or patent?

Our experienced attorneys are here to deliver results!

Contact Us or Call 972-248-8080 for a Free Consultation!

Have an idea for a blog? Click and request a blog and we will let you know when we post it!